We would reasonably expect that the amount of roads would be a good proxy for the cost of infrastructure : drains, water mains, sewerage pipes, electrical cables and telephone lines all run along roads – the shorter the road, the lower should be the length of the other services. To test out this out, we undertook to start comparing in detail the cost of water reticulation, sewerage piping, roads and drains in a honeycomb layout against that of a conventional layout.

REAL SITE COMPARISON

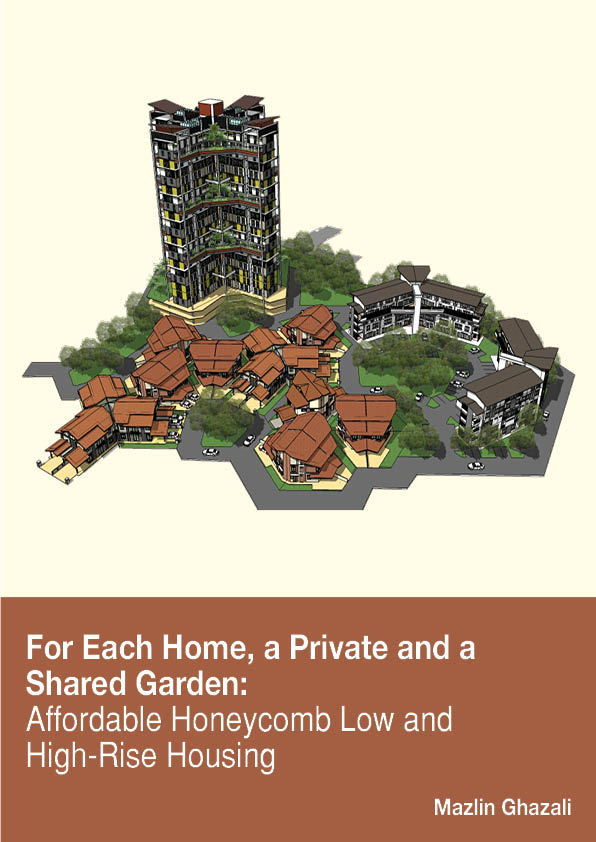

We approached Dato Eddie Chen, the CEO of a respected developer (Metro Kajang Bhd) to help us undertake a cost comparison between a rectilinear and honeycomb layout. He was sufficiently intrigued by the ‘honeycomb’ concept to participate in a research project to study the comparative cost of infrastructure of a ‘honeycomb’ layout. A control layout was adopted. This was the layout of a recently completed 60 acre housing scheme in Kajang, Bukit Mewah.

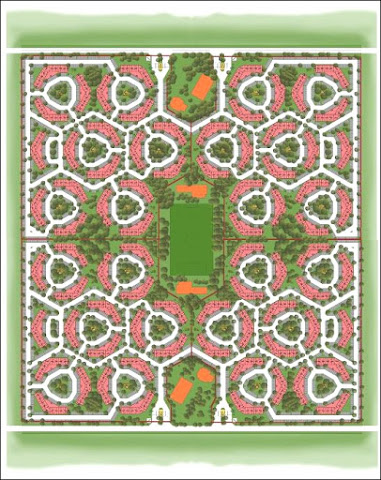

Figure 1

Given that Metro Kajang is a very experienced developer. Obviously, a lot of effort went into revenue out of every single square foot. The layout, as far as rectilinear developments go, is highly efficient. The developer made available to us the full set of layout plans, engineering drawings, Specifications and Bills of Quantities. A “Honeycomb”layout was prepared. We then had an Engineering Consultant, Perunding Metro (no connection with Metro Kajang Bhd.) under the direction of Ir. C.T. Sia, prepare the Sewerage, Water Reticulation and Roads and Drains drawings using the details and specifications adopted in the original design. In this way, a fair ‘apple to apple’ comparison could be undertaken. The quantities of the main items were then measured and the results tabulated for comparison. Edmund Foo, of Quantity Surveyors, JUB Segar then provided realistic rates to apply against the quantities.

RESULTS

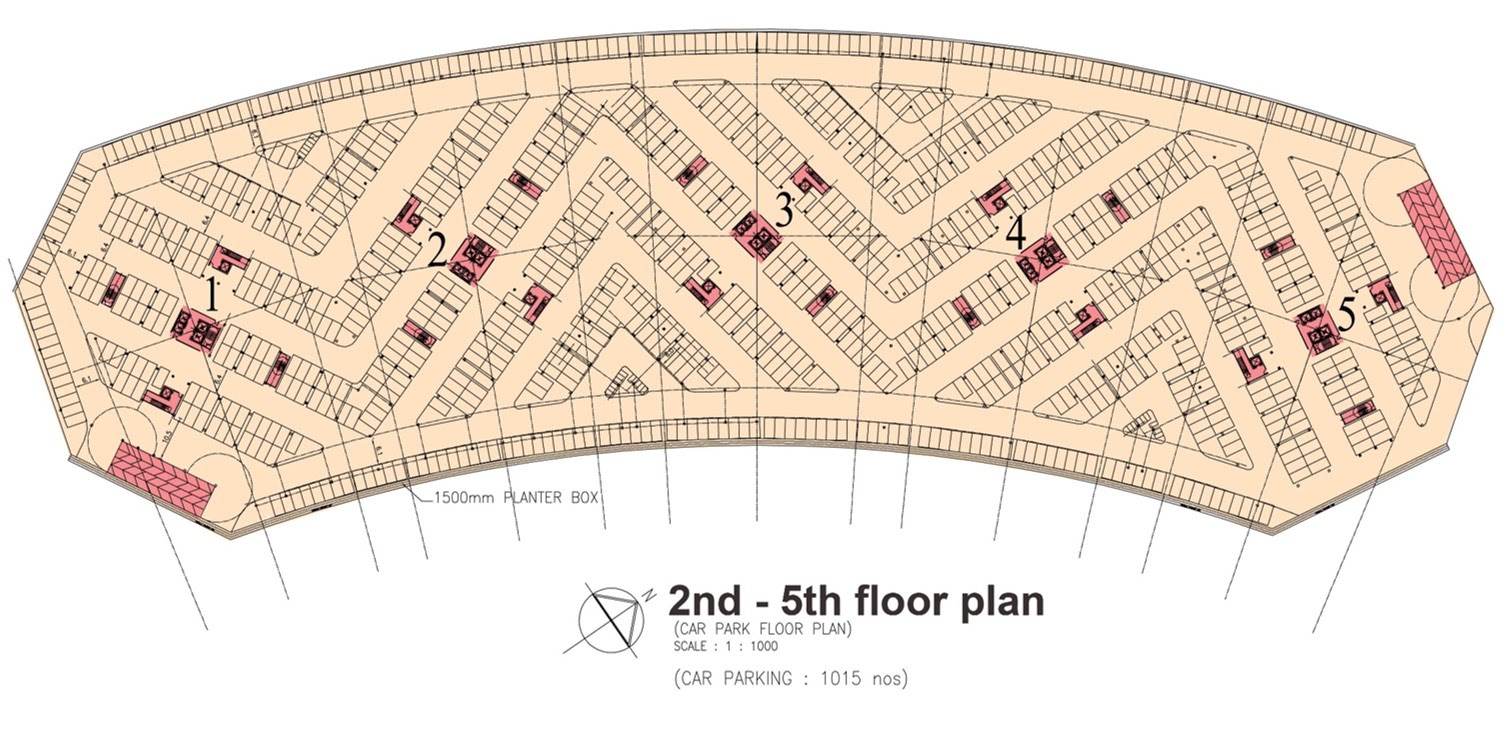

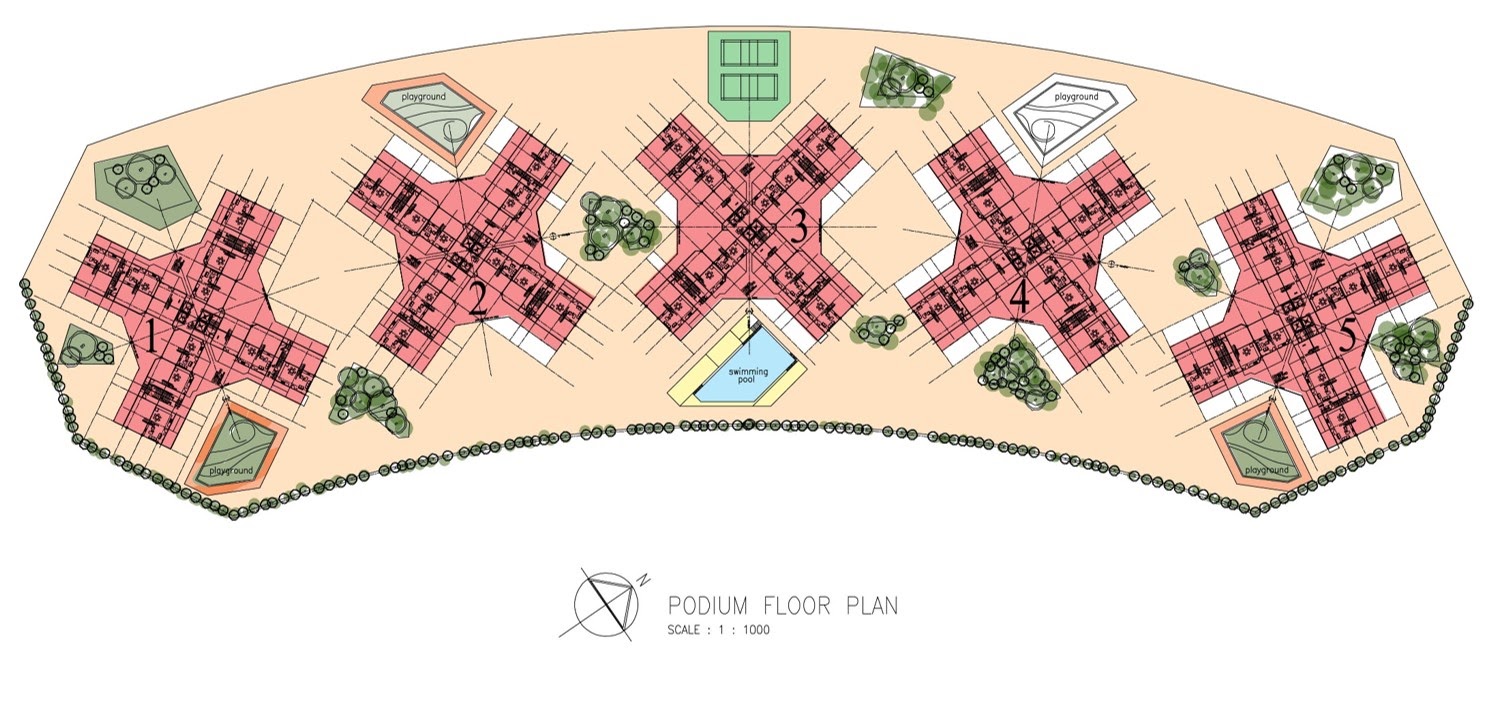

After completing the alternative honeycomb layout, a detailed breakdown of the land use was produced. Similarly, the drawing of the existing layout was subject to the same detailed breakdown. The drawings of the original and honeycomb layouts are given in figures 1 above. The detailed land-use breakdown of the two layout designs is shown in table 1.

The main results are shown below (table 2). The Saleable land in the honeycomb option is 23.92 acres compared to 23.21 acres in the original layout, an increase of 3.1%.

Table 2

Road Reserve (acres) | Green (acres) | Amenities (acres) | Units | ||

Original Built Option | 23.21 | 14.42 | 7.46 | 8.01 | 304 |

Honeycomb | 23.92 | 13.56 | 7.76 | 8.01 | 328 |

Increase/(decrease) | 0.71 | (0.86) | 0.3 | 0 | 24 |

% Increase/(decrease) | 3.1% | (6%) | 4% | 0% | 7.9% |

The land to be used as road reserve in the honeycomb option is 13.56 acres compared to 14.42 acres in the original layout, a reduction of 6%. The Green area is increased by 4%, whilst there is no change in the area of the Amenities. The number of units of landed property is increased from 304 to 328 units, up by 7.9%.

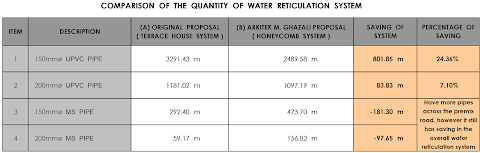

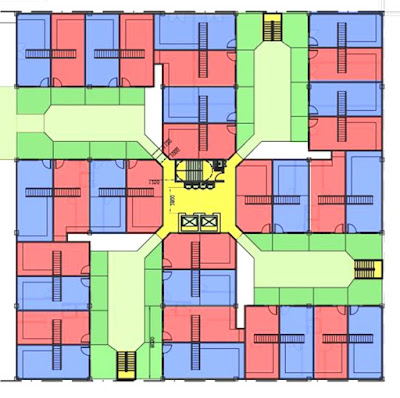

WATER RETICULATION SYSTEM

The main cost-centres picked up are 150mm and 200mm UPVC pipes and 150mm and 200mm mild steel (ms) pipes. The mild steel pipes are used where the pipes run below the premixed roads. The layouts of the built and honeycomb alternative options are given in figures 2 and the comparison is shown in table 4. There is an overall reduction in quantities for the honeycomb option; however there are more mild steel pipes.

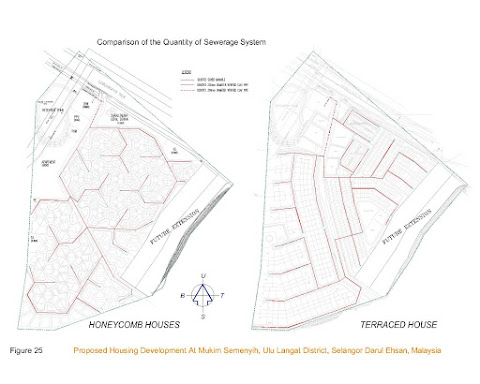

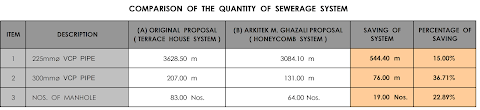

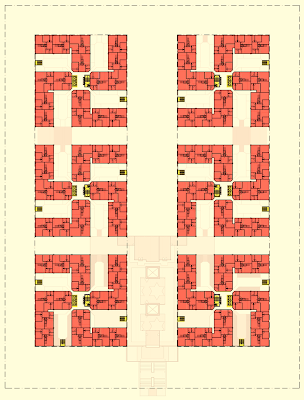

SEWERAGE SYSTEM

The main cost-centers picked up are 225mm and 300mm diameter Vitrified Clay Pipes (VCP) pipes and manholes. The layouts of the built and honeycomb alternative options are given in figures 3 (next pages) and the comparison is shown in table 5. There is an overall reduction in quantities for the honeycomb option. There is a 15% saving in the length of 225mm VCP pipes, a 37% reduction in 300mm diameter pipes and a 23% reduction in the number of manholes.

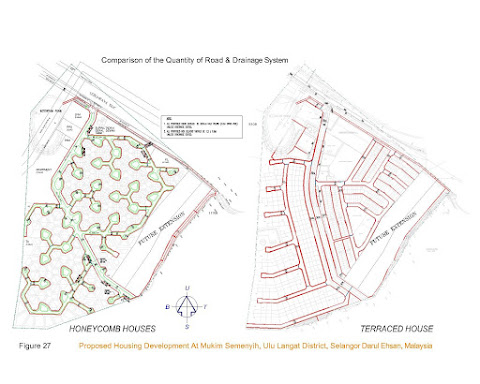

DRAINS

The main cost-centres picked up are drains and culverts. The drains are 0.6m wide, 0.9m wide and 1.2m wide. The culverts are 1.2mX 0.6m, 1.2X 0.9m and 1.8mX 1.2m. The layouts of the built and honeycomb alternative options are given in figures 4 (next few pages) and the comparison is shown in table 6. There is an overall reduction in quantities for the honeycomb option. There is a 10% saving in the length of 0.6m wide drains, a 57% increase in the 0.9m wide drains and a 58% reduction in the 1.2m wide drains. In addition, the length of the culverts were reduced – for the 1.2mX 0.6m, 25%; 1.2X 0.9m ,2%; and 1.8mX 1.2m, 31%.

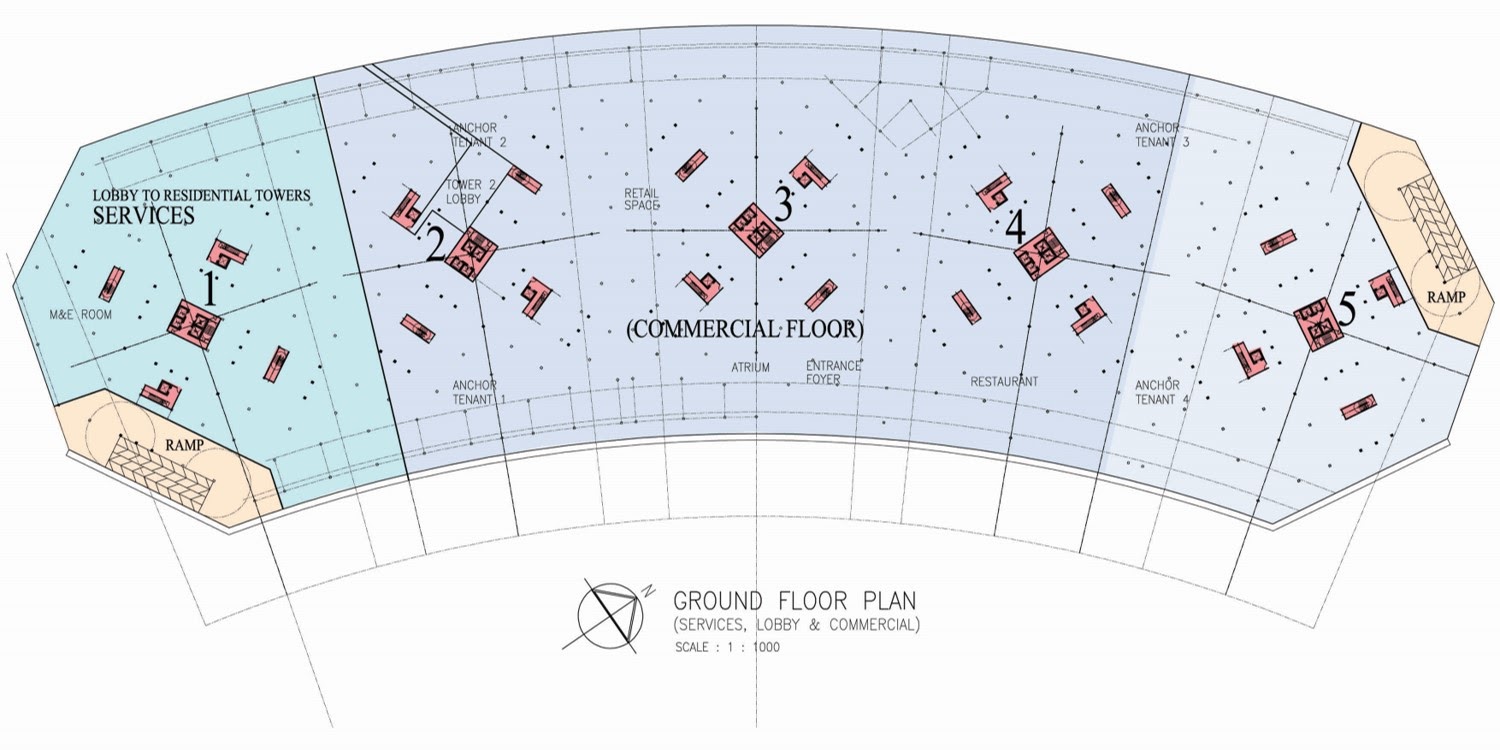

ROADS

The total area of the premixed road surface for both options were measured as follows – 28,799sm for the original option and 26,668sm for the honeycomb option. Refer to figures 5 and table 7 again. The honeycomb option saved 2,131sm of road surface.

Figure 4

Table 5

OVERALL COST COMPARISON

We found that the honeycomb layout produced lower cost figures for all the works compared with the conventional design (table 6 and 7).

For the Water Reticulation works, there is an overall reduction in quantities for the honeycomb option, however there are more mild steel pipes. Since the mild steel pipes are more expensive, overall, the cost of the honeycomb project is only cheaper by RM2508. I.e. only a 1% reduction in cost.

For the Sewerage works, there is an overall reduction in quantities for the honeycomb option. There is a 15% saving in the length of 225mm VCP pipes, a 37% reduction in 300mm diameter pipes and a 23% reduction in the number of manholes. Overall, the cost of the honeycomb proposal is cheaper by a substantial amount - RM126,941, i.e. a 19% reduction in cost .

For the Drainage works, there is a 10% saving in the length of 0.6m wide drains, a 57% increase in the 0.9m wide drains and a 58% reduction in the 1.2m wide drains. In addition, the length of the culverts were reduced – for the 1.2mX 0.6m, by 25%; 1.2X 0.9m ,by 2%; and 1.8mX 1.2m, 31%. Overall, the cost of the honeycomb project is cheaper by a substantial amount – RM181,500, i.e. a 13% reduction in cost .

For the Road works, the honeycomb option saved 2,131sm of road surface. The cost of the honeycomb proposal is cheaper by a substantial amount – RM102,301, i.e. a 7.4% reduction in cost.

The cost of the original design was RM3,688,618 compared to the honeycomb design, RM3,275,368. The honeycomb proposal turned out to be RM413,250 cheaper, a substantial 11% saving. However, there are more units in the honeycomb version – 328 instead of 304. This is an increase of 7.9%. Taken on per-unit basis, the savings in water reticulation, sewerage, roads and drains are as follows:

Table 7

Table 7

Total Cost (RM) | No of Units | Cost per unit (RM) | |

Original Built Option | 3,688,618 | 304 | 12,133.12 |

Honeycomb | 3,275,368 | 328 | 9,985.88 |

Table 6

DISCUSSION

It is interesting to note that the savings in the total area of road reserve is quite small. This amount is certainly less than that of the examples given earlier. I believe the reasons for this are as follows:

1 There are more units resulting in a higher density. These extra units bring down the area of road reserve per unit, and seen in this perspective, the reduction in roads becomes higher.

2 Only about a third of the layout is taken up by terrace houses. As shown earlier in the comparison between 3 and 8 units of detached units in a rectilinear layout versus the ‘honeycomb’ layout, there is a reduction in the amount of savings in roads. This is due to the absence of back-lanes in detached housing. In addition, the rectilinear layout of the detached lots employed a lot of cul-de-sacs which are land-use efficient.

3 The land designated for ‘future development’ was obviously shaped to take on continuing rows of terrace houses. A ‘honeycomb layout’ would have sliced out a different shape. As it is, the layout of ‘honeycomb’ houses at the periphery of the land for ‘future development’ became rather inefficient.

Given the small saving in road reserve area, the results become all the more remarkable. The roads pavement area itself saw a reduction of 7%. Quite substantial reductions were found for the cost of drains and culverts, sewerage pipes and manholes, and water mains.

Applying realistic rates to the outline bill of quantities, we found that the overall savings in the cost of the infrastructural services to be approximately RM413,250 or 11%, and the per-unit savings to be 17%.

Another factor to consider is the extra saleable land made available in the honeycomb layout. The extra land that can be sold is 0.71 acres or 30928 sf. If we price this land at RM50 per sf, the extra sale value unlocked will be RM 1,546,380.

CONCLUSION

From the studies undertaken above, we have found that the adoption of the ‘honeycomb’ layout has brought about clear improvements in land-use efficiency through a reduction in the area of roads. In the example, the reduction in the amount of roads, bring with it clear savings in the cost of roads, drains, water reticulation and sewerage lines. This example is, of course, based on a specific built project, and we cannot conclude that the employment of the ‘honeycomb’ layout will always give better results compared to rectilinear layouts. However, it has been shown that even in a case where the savings in amount of land used for road reserve is quite small, there is still substantial savings to be made in the infrastructure.

The reduction in roads brought about an increase in the saleable area. In this case study, the increase in saleable area is marginal, i.e. 3%. However the estimated contribution to the bottom line is a hefty RM 1.5 million, almost four times the estimated savings from infrastructure.

Certainly, the honeycomb technique has been shown to have its inherent advantages, and for developers tired of looking at rectilinear proposals, an honeycomb concept now presents a cost saving alternative. More than that, the benefits to be made from increasing sales revenue through having more land to sell, can be substantial.

Back to Table of Contents

Back to Table of Contents

GET A FREE HARDCOPY OF THIS BOOK IN FEBRUARY!!

Please help me proof-read this book. Just point out the errors in the comments section (look at the bottom left hand side of each post).

I'll post this book to the first reader who spots 5 mistakes...!

Please help me proof-read this book. Just point out the errors in the comments section (look at the bottom left hand side of each post).

I'll post this book to the first reader who spots 5 mistakes...!